|

A number of young catechumens were arrested, Revocatus and his fellow slave Felicitas, Saturninus and Secundulus, and with them Vibia Perpetua, a newly married woman of good family and upbringing. Her mother and father were still alive and one of her two brothers was a catechumen like herself. She was about twenty-two years old and had an infant son at the breast. Now from this point on the entire account of her ordeal is her own,

according to her own ideas and in the way that she herself wrote it

down. While we were still under

arrest (she said) my father out of love for me was trying to persuade

me and shake my resolution. 'Father,' said I, 'do you see this vase

here, for example, or waterpot or whatever?' 'Yes, I do', said he. And

I told him: 'Could it be called by any other name than what it is?' And

he said: 'No.' 'Well, so too I cannot be called anything other than

what I am, a Christian.' At this my father was so angered by the word

'Christian' that he moved towards me as though he would pluck my eyes

out. But he left it at that and departed, vanquished along with his

diabolical arguments. For a few days afterwards I

gave thanks to the Lord that I was separated from my father, and I was

comforted by his absence. During these few days I was baptized, and I

was inspired by the Spirit not to ask for any other favour after the

water but simply the perseverance of the flesh. A few days later we

were lodged in the prison; and I was terrified, as I had never before

been in such a dark hole. What a difficult time it was! With the crowd

the heat was stifling; then there was the extortion of the soldiers;

and to crown all, I was tortured with worry for my baby there. Then Tertius and Pomponius,

those blessed deacons who tried to take care of us, bribed the soldiers

to allow us to go to a better part of the prison to refresh ourselves

for a few hours. Everyone then left that dungeon and shifted for

himself. I nursed my baby, who was faint from hunger. In my anxiety I

spoke to my mother about the child, I tried to comfort my brother, and

I gave the child in their charge. I was in pain because I saw them

suffering out of pity for me. These were the trials I had to endure for

many days. Then I got permission for my baby to stay with me in prison.

At once I recovered my health, relieved as I was of my worry and

anxiety over the child. My prison had suddenly become a palace, so that

I wanted to be there rather than anywhere else. Then my brother said to me:

'Dear sister, you are greatly privileged; surely you might ask for a

vision to discover whether you are to be condemned or freed.'

Faithfully I promised that I would, for I knew that I could speak with

the Lord, whose great blessings I had come to experience. And so I

said: 'I shall tell you tomorrow.' Then I made my request and this was

the vision I had. I saw a ladder of

tremendous height made of bronze, reaching all the way to the heavens,

but it was so narrow that only one person could climb up at a time. To

the sides of the ladder were attached all sorts of metal weapons: there

were swords, spears, hooks, daggers, and spikes; so that if anyone

tried to climb up carelessly or without paying attention, he would be

mangled and his flesh would adhere to the weapons. At the foot of the ladder

lay a dragon of enormous size, and it would attack those who tried to

climb up and try to terrify them from doing so. And Saturus was the

first to go up, he who was later to give himself up of his own accord.

He had been the builder of our strength, although he was not present

when we were arrested. And he arrived at the top of the staircase and

he looked back and said to me: 'Perpetua, I am waiting for you. But

take care; do not let the dragon bite you.' 'He will not harm me,' I

said, 'in the name of Christ Jesus.' Slowly, as though he were afraid

of me, the dragon stuck his head out from underneath the ladder. Then,

using it as my first step, I trod on his head and went up. Then I saw an immense

garden, and in it a gray-haired man sat in shepherd's garb; tall he

was, and milking sheep. And standing around him were many thousands of

people clad in white garments. He raised his head, looked at me, and

said: 'I am glad you have come, my child.' He called me over to him and

gave me, as it were, a mouthful Of the milk he was drawing; and I took

it into my cupped hands and consumed it. And all those who stood around

said: 'Amen!' At the sound of this word I came to, with the taste of

something sweet still in my mouth. I at once told this to my brother,

and we realized that we would have to suffer, and that from now on we

would no longer have any hope in this life. A few days later there was

a rumor that we were going to be given a hearing. My father also

arrived from the city, worn with worry, and he came to see me with the

idea of persuading me. 'Daughter,' he said, 'have pity on my grey

head--have pity on me your father, if I deserve to be called your

father, if I have favored you above all your brothers, if I have

raised you to reach this prime of your life. Do not abandon me to be

the reproach of men. Think of your brothers, think of your mother and

your aunt, think of your child, who will not be able to live once you

are gone. Give up your pride! You will destroy all of us! None of us

will ever be able to speak freely again if anything happens to you.'

This was the way my father spoke out of love for me, kissing my hands

and throwing himself down before me. With tears in his eyes he no

longer addressed me as his daughter but as a woman. I was sorry for my

father's sake, because he alone of all my kin would be unhappy to see

me suffer. I tried to comfort him saying: 'It will all happen in the

prisoner's dock as God wills; for you may be sure that we are not left

to ourselves but are all in his power.' And he left me in great sorrow. One day while we were

eating breakfast we were suddenly hurried off for a hearing. We arrived

at the forum, and straight away the story went about the neighborhood

near the forum and a huge crowd gathered. We walked up to the

prisoner's dock. All the others when questioned admitted their guilt.

Then, when it came my turn, my father appeared with my son, dragged me

from the step, and said: 'Perform the sacrifice--have pity on your

baby!' Hilarianus the governor, who had received his judicial powers as

the successor of the late proconsul Minucius Timinianus, said to me:

'Have pity on your father's grey head; have pity on your infant son.

Offer the sacrifice for the welfare of the emperors.' 'I will not', I

retorted. 'Are you a Christian?' said Hilarianus. And I said: 'Yes, I

am.' When my father persisted in trying to dissuade me, Hilarianus

ordered him to be thrown to the ground and beaten with a rod. I felt

sorry for father, just as if I myself had been beaten. I felt sorry for

his pathetic old age. Then Hilarianus passed sentence on all of us: we

were condemned to the beasts, and we returned to prison in high

spirits. But my baby had got used to being nursed at the breast and to

staying with me in prison. So I sent the deacon Pomponius straight away

to my father to ask for the baby. But father refused to give him over.

But as God willed, the baby had no further desire for the breast, nor

did I suffer any inflammation; and so I was relieved of any anxiety for

my child and of any discomfort in my breasts. Some days later, an

adjutant named Pudens, who was in charge of the prison, began to show

us great honor, realizing that we possessed some great power within

us. And he began to allow many visitors to see us for our mutual

comfort. Now the day of the contest

was approaching, and my father came to see me overwhelmed with sorrow.

He started tearing the hairs from his beard and threw them on the

ground; he then threw himself on the ground and began to curse his old

age and to say such words as would move all creation. I felt sorry for

his unhappy old age. The day before we were to

fight with the beasts I saw the following vision. Pomponius the deacon

came to the prison gates and began to knock violently. I went out and

opened the gate for him. He was dressed in an unbelted white tunic,

wearing elaborate sandals. And he said to me: 'Perpetua, come; we are

waiting for you.' Then he took my hand and we began to walk through

rough and broken country. At last we came to the amphitheatre out of

breath, and he led me into the centre of the arena. Then he told me:

'Do not be afraid. I am here, struggling with you.' Then he left. I

looked at the enormous crowd who watched in astonishment. I was

surprised that no beasts were let loose on me; for I knew that I was

condemned to die by the beasts. Then out came an Egyptian against me,

of vicious appearance, together with his seconds, to fight with me.

There also came up to me some handsome young men to be my seconds and

assistants. My clothes were stripped off, and suddenly I was a man. My

seconds began to rub me down with oil (as they are wont to do before a

contest). Then I saw the Egyptian on the other side rolling in the

dust. Next there came forth a man of marvelous stature, such that he

rose above the top of the amphitheatre. He was clad in a beltless

purple tunic with two stripes (one on either side) running down the

middle of his chest. He wore sandals that were wondrously made of gold

and silver, and he carried a wand like an athletic trainer and a green

branch on which there were golden apples. And he asked for silence and

said: 'If this Egyptian defeats her he will slay her with the sword.

But if she defeats him, she will receive this branch.' Then he

withdrew. We drew close to one another and began to let our fists fly.

My opponent tried to get hold of my feet, but I kept striking him in

the face with the heels of my feet. Then I was raised up into the air

and I began to pummel him without as it were touching the ground. Then

when I noticed there was a lull, I put my two hands together linking

the fingers of one hand with those of the other and thus I got hold of

his head. He fell flat on his face and I stepped on his head. The crowd

began to shout and my assistants started to sing psalms. Then I walked

up to the trainer and took the branch. He kissed me and said to me:

'Peace be with you, my daughter!' I began to walk in triumph towards

the Gate of Life. Then I awoke. I realized that it was not with wild

animals that I would fight but with the Devil, but I knew that I would

win the victory. So much for what I did up until the eve of the

contest. About what happened at the contest itself, let him write of it

who will. [Here Saturus tells the

story of a vision he had of Perpetua and himself, after they were

killed, being carried by four angels into heaven where they were

reunited with other martyrs killed in the same persecution.] [Here the

editor/narrator begins to relate the story]: Such were the remarkable

visions of these martyrs, Saturus and Perpetua, written by themselves.

As for Secundulus, God called him from this world earlier than the

others while he was still in prison, by a special grace that he might

not have to face the animals. Yet his flesh, if not his spirit, knew

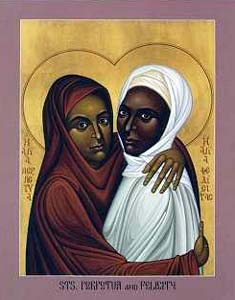

the sword. As for Felicitas, she too

enjoyed the Lord's favor in this wise. She had been pregnant when she

was arrested, and was now in her eighth month. As the day of the

spectacle drew near she was very distressed that her martyrdom would be

postponed because of her pregnancy; for it is against the law for women

with child to be executed. Thus she might have to shed her holy,

innocent blood afterwards along with others who were common criminals.

Her comrades in martyrdom were also saddened; for they were afraid that

they would have to leave behind so fine a companion to travel alone on

the same road to hope. And so, two days before the contest, they poured

forth a prayer to the Lord in one torrent of common grief. And

immediately after their prayer the birth pains came upon her. She

suffered a good deal in her labor because of the natural difficulty of

an eight months' delivery. Hence one of the assistants

of the prison guards said to her: 'You suffer so much now--what will

you do when you are tossed to the beasts? Little did you think of them

when you refused to sacrifice.' 'What I am suffering now', she replied,

'I suffer by myself. But then another will be inside me who will suffer

for me, just as I shall be suffering for him.' And she gave birth to a

girl; and one of the sisters brought her up as her own daughter. Therefore, since the Holy

Spirit has permitted the story of this contest to be written down and

by so permitting has willed it, we shall carry out the command or,

indeed, the commission of the most saintly Perpetua, however unworthy I

might be to add anything to this glorious story. At the same time I

shall add one example of her perseverance and nobility of soul. The military tribune had

treated them with extraordinary severity because on the information of

certain very foolish people he became afraid that they would be

spirited out of the prison by magical spells. Perpetua spoke to him

directly. 'Why can you not even allow us to refresh ourselves properly?

For we are the most distinguished of the condemned prisoners, seeing

that we belong to the emperor; we are to fight on his very birthday.

Would it not be to your credit if we were brought forth on the day in a

healthier condition?' The officer became disturbed and grew red. So it

was that he gave the order that they were to be more humanely treated;

and he allowed her brothers and other persons to visit, so that the

prisoners could dine in their company. By this time the adjutant who

was head of the jail was himself a Christian. On the day before, when

they had their last meal, which is called the free banquet, they

celebrated not a banquet but rather a love feast. They spoke to the mob

with the same steadfastness, warned them of God's judgment, stressing

the joy they would have in their suffering, and ridiculing the

curiosity of those that came to see them. Saturus said: 'Will not

tomorrow be enough for you? Why are you so eager to see something that

you dislike? Our friends today will be our enemies on the morrow. But

take careful note of what we look like so that you will recognize us on

the day.' Thus everyone would depart from the prison in amazement, and

many of them began to believe. The day of their victory

dawned, and they marched from the prison to the amphitheatre joyfully

as though they were going to heaven, with calm faces, trembling, if at

all, with joy rather than fear. Perpetua went along with shining

countenance and calm step, as the beloved of God, as a wife of Christ,

putting down everyone's stare by her own intense gaze. With them also

was Felicitas, glad that she had safely given birth so that now she

could fight the beasts, going from one blood bath to another, from the

midwife to the gladiator, ready to wash after childbirth in a second

baptism. They were then led up to

the gates and the men were forced to put on the robes of priests of

Saturn, the women the dress of the priestesses of Ceres. But the noble

Perpetua strenuously resisted this to the end. 'We came to this of our

own free will, that our freedom should not be violated. We agreed to

pledge our lives provided that we would do no such thing. You agreed

with us to do this.' Even injustice recognized justice. The military

tribune agreed. They were to be brought into the arena just as they

were. Perpetua then began to sing a psalm: she was already treading on

the head of the Egyptian. Revocatus, Saturninus, and Saturus began to

warn the on looking mob. Then when they came within sight of Hilarianus,

they suggested by their motions and gestures: 'You have condemned us,

but God will condemn you' was what they were saying. At this the crowds became

enraged and demanded that they be scourged before a line of gladiators.

And they rejoiced at this that they had obtained a share in the Lord's

sufferings. But he who said, Ask and

you shall receive, answered their prayer by giving each one the death

he had asked for. For whenever they would discuss among themselves

their desire for martyrdom, Saturninus indeed insisted that he wanted

to be exposed to all the different beasts, that his crown might be all

the more glorious. And so at the outset of the contest he and Revocatus

were matched with a leopard, and then while in the stocks they were

attacked by a bear. As for Saturus, he dreaded nothing more than a

bear, and he counted on being killed by one bite of a leopard. Then he

was matched with a wild boar; but the gladiator who had tied him to the

animal was gored by the boar and died a few days after the contest,

whereas Saturus was only dragged along. Then when he was bound in the

stocks awaiting the bear, the animal refused to come out of the cages,

so that Saturus was called back once more unhurt. For the young women,

however, the Devil had prepared a mad heifer. This was an unusual

animal, but it was chosen that their sex might be matched with that of

the beast. So they were stripped naked, placed in nets and thus brought

out into the arena. Even the crowd was horrified when they saw that one

was a delicate young girl and the other was a woman fresh from

childbirth with the milk still dripping from her breasts. And so they

were brought back again and dressed in unbelted tunics. First the heifer tossed

Perpetua and she fell on her back. Then sitting up she pulled down the

tunic that was ripped along the side so that it covered her thighs,

thinking more of her modesty than of her pain. Next she asked for a pin

to fasten her untidy hair: for it was not right that a martyr should

die with her hair in disorder, lest she might seem to be mourning in

her hour of triumph. Then she got up. And seeing

that Felicitas had been crushed to the ground, she went over to her,

gave her hand, and lifted her up. Then the two stood side by side. But

the cruelty of the mob was by now appeased, and so they were called

back through the Gate of Life. There Perpetua was held up

by a man named Rusticus who was at the time a catechumen and kept close

to her. She awoke from a kind of sleep (so absorbed had she been in

ecstasy in the Spirit) and she began to look about her. Then to the

amazement of all she said: 'When are we going to be thrown to that

heifer or whatever it is?' When told that this had already happened,

she refused to believe it until she noticed the marks of her rough

experience on her person and her dress. Then she called for her brother

and spoke to him together with the catechumens and said: 'You must all

stand fast in the faith and love one another, and do not be weakened by

what we have gone through.' At another gate Saturus was

earnestly addressing the soldier Pudens. 'It is exactly', he said, 'as

I foretold and predicted. So far not one animal has touched me. So now

you may believe me with all your heart: I am going in there and I shall

be finished off with one bite of the leopard.' And immediately as the

contest was coming to a close a leopard was let loose, and after one

bite Saturus was so drenched with blood that as he came away the mob

roared in witness to his second baptism: 'Well washed! Well washed!'

For well washed indeed was one who had been bathed in this manner. Then

he said to the soldier Pudens: 'Good-bye. Remember me, and remember the

faith. These things should not disturb you but rather strengthen you.' And with this he asked

Pudens for a ring from his finger, and dipping it into his wound he

gave it back to him again as a pledge and as a record of his bloodshed.

Shortly after he was thrown unconscious with the rest in the usual spot

to have his throat cut. But the mob asked that their bodies be brought

out into the open that their eyes might be the guilty witnesses of the

sword that pierced their flesh. And so the martyrs got up and went to

the spot of their own accord as the people wanted them to, and kissing

one another they sealed their martyrdom with the ritual kiss of peace.

The others took the sword in silence and without moving, especially

Saturus, who being the first to climb the stairway was the first to

die. For once again he was waiting for Perpetual Perpetua, however, had

yet to taste more pain. She screamed as she was struck on the bone;

then she took the trembling hand of the young gladiator and guided it

to her throat. It was as though so great a woman, feared as she was by

the unclean spirit, could not be dispatched unless she herself were

willing. Ah, most valiant and

blessed martyrs! Truly are you called and chosen for the glory of

Christ Jesus our Lord! And any man who exalts, honors, and worships

his glory should read for the consolation of the Church these new deeds

of heroism which are no less significant than the tales of old. For

these new manifestations of virtue will bear witness to one and the

same Spirit who still operates, and to God the Father almighty, to his

Son Jesus Christ our Lord, to whom is splendor and immeasurable power

for all the ages. Amen.

|

LETTERS BETWEEN THE CHURCHESOF ROME AND OF CARTHAGEIn telling the story of the Catacombs of St. Callixtus we have met personalities of the highest order: the martyr popes Fabian, Cornelius, Sixtus II...and the bishop of Carthage St. Cyprian. The Church of Rome and that of Carthage were often in contact. It is interesting to know the contents of some letters, to be acquainted with what those great Pastors talked about and how they judged their times, which were anything but tranquil.1. The Church of Rome to the Church of Carthage The Church of Rome, during the persecution of emperor Decius, offered to the Church of Carthage the following testimonial of its faithfulness to Christ. Rome, early 250. " ... The Church resists strong in the faith. It is true that some have yielded, being alarmed at the possibility that their high social position might attract attention, or from simple human frailty. Nevertheless, though they are now separated from us, we have not abandoned them in their defection, but have helped them and keep still close to them, so that by penance they may be rehabilitated and pardoned by Him who can forgive. Indeed if we were to leave them to their own resources, their fall would become irreparable. Try and do the same, dearest brothers, extending your hand to those who have fallen, that they may rise again. Thus, if they should be arrested, they may this time feel strong enough to confess the faith and redress their former error. Allow me also to remind you of what course to take on another problem. Those who surrendered in the time of trial, and are now ill and have repented and want communion with the Church, should be helped. Widows and other persons unable to present themselves spontaneously, as also those in prison or far from home, ought to have people ready to look after them. Nor should catechumens who have fallen ill remain disappointed in their expectation of help. The brethren who are in prison, the clergy and the entire Church, that watches so carefully over those who call on the Lord's name, salute you. In return we also ask you to remember us" (letter 8,2-3). 2. The Bishop of Carthage to the Church of Rome When Cyprian was informed of pope Fabian's death, he wrote this letter to the priests and deacons in Rome. Carthage, early 250.. "My dear brothers, News of the death of my saintly fellow-bishop was still uncertain and information doubtful, when I received your letter brought by subdeacon Crementius, telling me fully of his glorious death. Then I rejoiced, as his admirable governing of the Church had been followed by a noble end. For this I share your gladness, as you the memory of so solemn and splendid a witness, communicating to us also the glorious recollection you have of your bishop, and offering us such an example of faith and fortitude. Indeed, harmful as the fall of a leader is to his subjects, no less valuable and salutary for his brethren is the example of a bishop firm in his faith... My wish, dearest brothers, is for your continued welfare" (Letter 1). 3. Cyprian, bishop of Carthage to pope Cornelius Ciprian pays homage to the testimony and fidelity shown by the Pope Cornelius and by the Church of Rome: " a magnificent testimony of a Church entirely united in one spirit and one voice". Foreseeing an imminent time of trial also for the Church of Carthage, Cyprian asks for the brotherly help of prayer and charity. Carthage, autumn 153.. "Cyprian to Cornelius, his brother bishop. We know, dearest brother, of your faith, your fortitude and your open witness. All this does you great honor and it gives me so much joy that I feel myself part of and companion in your merits and undertakings. Since indeed the Church is one, and one and inseparable is love, and one and unbreakable is the harmony of hearts, what priest singing the praises of another does not rejoice as though they were his own glory? And what brother would not feel happy at the joy of his brethren? Certainly none can imagine the exultation and great joy there has been among us here when we have learnt such fine things, like the proofs of strength you have given.

You have led your brethren to testify their faith, and that very

confession of yours has been strengthened further by that of the

brethren. Thus, while you have gone before the others in the path of

glory, and have shown yourself ready to be the first in testifying

for all, you have persuaded the people too to confess the same

faith.

|

|

1. From

the Letter to Diognetus (apology by an unknown author of the

2nd C.). |