|

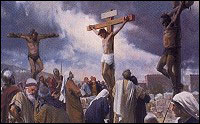

Confirmation Regarding the Crucifixion

All four Gospels give details of the crucifixion of

Christ. Their accurate portrayal of this Roman practice has

been confirmed by archaeology. In 1968, building contractors

found four cave-tombs at Giv'at ha-Mivtar (Ras el-Masaref),

which is just north of Jerusalem near Mount Scopus and

immediately west of the road to Nablus was uncovered.

Within the caves were found fifteen limestone ossuaries

which contained the bones of thirty-five individuals. Nine

of the thirty-five individuals had met violent death. One of

these, a man between twenty-four and twenty-eight years of

age was crucified.

The name of the man was incised on his ossuary in letters

2 cm high: Jehohanan. He was crucified probably between A.D.

7, the time of the census revolt, and 66, the beginning of

the war against Rome.

Heelbones found

The practice dates back to at least 500

B.C., first coming into use in the Middle East via Persia

and Egypt. The

Romans, who may have borrowed it from Carthage, reserved it

for slaves and despised malefactors. Crucifixion was

particularly effective in sending a message to seditious

populations concerning the likely fate of those who tamper

with authority. It was common practice among the

Romans to scourge the prisoner and to require him to carry

his cross to the place of crucifixion. The prisoner was

either nailed or tied to the cross, and, to induce more

rapid death, his legs were often broken.

Maxtin Mengel, wrote what is perhaps the definitive

scholarly report of the subject of Crucifixion in antiquity,

argues that nailing the victim by both hands and feet was

the rule and tying the victim to the cross was the

exception. During the first revolt of the Jews against the

Romans in AD 66-73, Josephus mentions that in the fall of

Jerusalem (AD 70), "the soldiers out of rage and hatred

amused themselves by nailing their prisoners in

different postures." |

|